Four Progresses Mha 1st Case

Four Progresses in The First Case of Mental Health Law of China

author: Yang Weihua Lawyer

source in Chinese (Lawyer Yang’s Wechat post

(This is just a translation by meaning. There are some words added and ignored by translator.)

Some background information:

The plaintiff of the first case in Mental Health Law of China, Xu Wei, is a man who has been committed to psychiatric hospital and institutions for about 14 years (from 2002 to 2017). When Mental Health Law was enacted in May of 2013, Xu Wei was able to ask for dischargement with the assistance of lawyer Yang and a dedicated NGO. Even though the MHL set explicitly the patient’s right to sue as well as their right to discharge by themselves (in the situation of no dangerousness), the persons with psychosocial(mental) disabilities can still be entitled as incapacitated or limited capacitated before the law. This is mainly regulated in civil laws of China. Thus, Xu Wei and lawyer Yang started their five-year long journey to fight for his right to discharge.

Lawyer Yang’s reflection:

First progress, was the enforcement of Shanghai Mental Health Ordinance in 2002 (Xu lives in Shanghai). At that time Xu had been living in the mental health center in Putuo District, Shanghai for one year. It seemed that there’s little hope of dischargement for him.

Fortunately, there was a first of its kind of mental health (local) regulation had been released in Shanghai in the same year, April the 7th. It breakingly set up a mechanism of diagnosis, hospitalization, forensics and rehabilitation for “psychiatric patients”in mental health services based on a psyhchiatric concept of “insight” as a core of its mechanism.

From the perspectives today, it was problematic for this regulation to introduce this psychiatric concept into the law/regulation area, as well as its article which said: “patients’ rights to informed consent and decision-making should only be valid under the premise that he or she has insight.” (article 36) However, this regulation had also clarified explicitly that “psychiatric patients”’s rights should be protected. It said: “medical institutions should approve the request to discharge by patients who has insight.” (article 33)

Under this circumstance, Xu received a notice from his institution telling him that he can be discharged one day. And then he went home by himself.

Second progress, was the enactment of Mental Health Law of China (markably its Article 82), on May 1st, 2013.

By then, Xu had been hospitalized in an private institution called Shanghai Qingchun institution for mental rehabilitation for ten years. In ten years time, he had tried various ways to leave the institution, such as run-away, and a law suit for changing his guardianship. But all of them failed. It seemed that the possibility to fly over the wall of the institution became harder and harder!

Another fortune came to him. The first Mental Health Law of China went into force in that year. Its Article 82 said: “patient with mental disability/disorder or his/her guardian or close relatives can initiate a litigation if he/she thinks his/her rights are violated according to this law by administrative, medical or other parties.” This article parallels the three subjects which explicitly shows that persons with mental disability/disorder have the right to sue. Although there was no any laws or regulations that deny the right to access to justice of the persons with mental disability/disorder, it was a significant milestone that their right to sue had been explicitly declared as the first in Chinese laws.

By far, as we all know, persons with psychosocial disabilities still face the difficulty of access to litigation. Though our friends with psychosocial disabilities should take advantage of the Article 82 which will be really useful. Xu Wei had been able to sue on the first day of the enactment of Mental Health Law, just because of this article. After that, it had been seven month later that his case was accepted by the court. I (lawyer Yang) had been explained so much to the court during that time. According to the Article 82, the right to sue of the persons with disability/disorder is assured and can not be deprived by the court. As for the right to proxy, the guardian as a defendant should not be the guardian/proxy of the plaintiff in the same case - according to the principles of the right of proxy in Civil Rules of China. The court sould recognize the plaintiff’s right of choosing a lawyer to represent him/her according to his/her pure income behavior. I knew that the court would not have such patience to deal with my case without the Article 82, even though I myself was knowledgable enough on this (and so was the court).

Third progress, was the amendment of Shanghai Mental Health Ordinance in March 1st, 2015 (esp. Article 41).

When time flies to 2015, Xu had failed the first court trial of this case (first case in Mental Health Law), and he began the procedure of appealing. I (lawyer Yang) and Xu did not feel optimistic about its result. My opinions were stated on my statement for appealing: “There are two focal points of this case: for one, is apellant’s behavior danger to himself and/or others? for the other, does the apellant have the right as well as the capacity/ability to discharge by himself?” For the first point, I argued that the apellee had mixed up with the concepts of dangerousness and probability; for the second point, the Article 45 of Mental Health Law already states that “For psychiatric patients who are to be discharged, if they had no capacity/ability to do that, their guardians should take the procedure of dischargement for them”. This implies that the psychiatric patients can take the procedure of dischargement by themselves, as long as they have the ability to do that.

As for this implication, there was already a law which is the just amended Shanghai Mental Health Ordinance on my back. This local regulation had inititated its amendment right after the enactment of Mental Health Law. On March 1st 2015, the updated version went into force. It explicitly states the logic that the Article 45 of Mental Health Law implies. It refines the logic as: “In-patient psychiatric patients who meet the condition of dischargement, should take their procedure for discharge in time. The patients can take the procedure for discharge by themselves as well as by their guardians; Patients who have no ability to take the procedure for discharge, their guardians should take that procedure for them.”

However, unfortunately, the second trial failed mistakenly again. The court utilized the General Civil Law over Mental Health Law. But I still feel confident since the amended Shanghai Mental Health Ordinance definitely strengthens my arguement.

Forth progress, is the enactment of the General Principles of Civil Law (民法总则) on October 1st, 2017 (especially the Article 24).

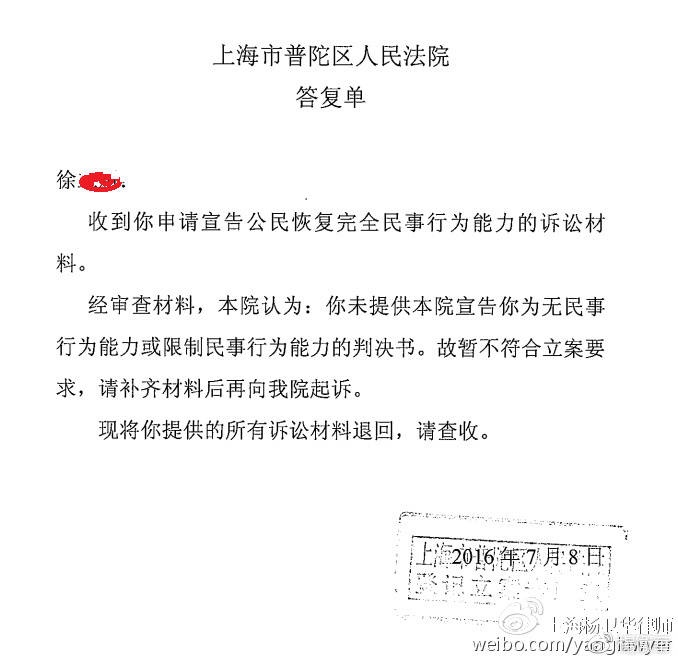

The time flies to the first half of 2016, the first case of Mental Health Law has gone through its first trial, second trial, retrial and the application for counterappeal, whereas we failed in all these processes. But Xu Wei did not give up, and tried to apply the psychiatric forensics for the third time. He was then very determined and said that if this try went failure again, he will stop his life. I, as his legal-aid lawyer, was deeply moved and encouraged by him. I tried again and again to negotiate with the local court (Putuo District, where Xu’s household registered), trying to put this case on record in order to apply for a psychiatric forensics, with a suitable cause of action. The process lasted about half a year. We used three possible causes of action. One of them was that Xu himself applies for a declaration of fully capacitated person to him. But the court rejected it with an incredible reason. (see the photo)

The logic on the reply from the Court of Putuo District can be concluded as: the court can not declare that Xu is a person of capacity because the previous (2012) verdict of the case related to Xu can not be considered as a verdict that declears you (Xu) were/are a person of incapacity or limited capacity. Although the previous verdict de facto recognized that Xu was a person of capacity, the cause of action of that case was to change his guardian but not to declare his capacity. Therefore the court alleged they have no privilege to do that (and also Xu cannot provide other verdict which declares he is a person of capacity).

Such logic sounds reasonable, from the perspective of those judges who adopt “ostrich policy” to their cases. The previous (unamended) Civil Law (民法通则) regulated that the stakholders of the psychiatric patient can apply for declaration that the patient is a person of incapacity or limited capacity before the court. The person who was declared as incapacitated or limited capacitated, can by himself/herself or by stakeholders apply for declaration that he/she is a person of limited capacity or full capacity before the court. Article 187 and 190 of Civil Procedure Law also state the procedure of the declaration of capacity/incapacity.

However, problematically, there are massive persons with psychosocial disabilities and persons with intellectual/learning disabilities being treated as persons of limited capacity (or persons of incapacity) in front of various organizations/institutions by various reasons, not declared by the court. Mr. Xu is the case. He had been treated as limited capacitated person by the local hospital for ten years before he received the judgement of declaring him a limited capacitated person by Putuo District Court in 2012. During this ten years he had been designated a guardian by the local authority (居委会). And during this ten years he had been isolated within the wall of a private mental institution for “rehabilitation”, with his liberty fully deprived.

So the tricky thing is, according to the logic of Putuo District Court, what on earth capacity does Xu have? Is he a legitimate limited capacitated person, or is he still a capacitated person since no legal procedure has declared that he is not? Now the society/community will not recognize his capacity in fact, and how will he find ways to resume his personhood about capacity which has been somehow lost?

You know what, the court will not think of such things. We had to change to the third cause to action (which was that we represented Xu’s mother to apply for disable her guardianship to the court). The court finally accepted the case. Thus Xu was able to apply for his third psychiatric forensics. And God blessed, we received the result of the forensics which recognized Xu’s full capacitated personhood. Therefore, there was no need to take the action to disable his guardianship. We then asked the court to declare that Xu was a person of full capacity with this forensics result as an evidence. But there was still the old dilemma: Why and how would the court declare Xu was fully capacitated while nobody had declared that he was not?

Let’s not worry, at last! The amended General Principles of Civil Law (民法总则) helps us. Its Article 24 changes the term “declare” (in Article 19 of Civil Law) to “recognize” when it comes to state the procedure of judging a person’s capacity. This indicates that the declaration of incapacity is not the premise of the declaration of capacity. The court can recognize the person’s capacity based only at any explicitly or implicitly stated recognition of the person’s incapacity in previous judgements. According to this change, Putuo District Court had to made the judgement of declaring Xu’s full capacity on October, while it accepted our application as early as on August this year.

Till now, the first case of Mental Health Law has been finished. Mr. Xu can start his brand new life freely along with his girlfriend (who has also been cimmitted to the same mental institution for many years).

translator: Regaudit

(Proofreading needed)

This article is released under CC BY-ND-SA 4.0